- 二系統の福富草紙~二巻本と一巻本の成立~

-

Two Versions of Fukutomi Zoshi: Formation of a two-volume scroll and one-volume scrollTwo Versions: Two-volume scroll and one-volume scroll

B version 5th paragraph

B version 5th paragraphFukutomi Zoshi is a comedy set in Kyoto that depicts an old man who is successful at the art of farting, and another old man living next door who tries to imitate him but fails. The picture scroll that serves as the manuscript for this story is thought to have been originated in the mid-15thcentury of the Muromachi period, and drawn and transcribed over the next 400 years.

In this transcription process, a variety of versions of Fukutomi Zoshi were born. The largest difference was that it is broadly divided into two versions, one that is made up of two volumes, and where the story progresses through dialogues between the characters, and another version that is comprised of only the second volume, where the story progresses mainly through a descriptive narrative.

First, let’s analyze the works that were produced the earliest, and look at the circumstances at the time when Fukutomi Zoshi was created as a picture scroll. Hyogo Prefectural Museum of History Collection

Hyogo Prefectural Museum of History Collection

Left: A version

(One-volume scroll)

Right: B version

(Second part of two-volume scroll)Among the manuscripts, the ones that are by far the oldest are the ones at Shunpo-in and the Cleveland Museum of Art.

Based on the painting style, both are thought to have been produced roughly in the mid-15th century, and the general opinion is that the scroll at the Cleveland Museum of Art is thought to have been produced slightly later (*01). Neither of the scrolls is signed by the artist or the transcriber. However, it has been pointed out that the design is similar to preceding, prominent picture scrolls Ishiyama-dera Engi Emaki (picture scrolls of Ishiyama Temple’s histories) and Yuzu Nenbutsu Engi Emaki (picture scroll of the origins of the Yuzu Nenbutsu sect), and thus, it is speculated that the artist is the same or a disciple of the same school (*02).

On the other hand, there are omissions of drawing motifs, phrases in the legend, etc., in both the Shunpo-in and Cleveland Museum of Art scrolls, which are the oldest, and thus, both are thought to be transcriptions of Fukutomi Zoshi, rather than original versions (*03).

Around this time, the legend at the opening of the two-volume version of Fukutomi Zoshi was transcribed by Sadafusa Shinno (*04). This transcription is dated a little before 1452. Sadafusa was the father of Go-Hanazono (1428-1364), who reigned as Emperor at the time.

At around the same time, the daughter of Takamuko no Hidetake, who is the central character of the two-volume version of Fukutomi Zoshi, appeared in a separate picture scroll as an old priestess (where she is around an age when her father was active in the art of farting). There is a postscript by Gogatsubi in 1449 in a picture scroll entitled Hohi Gassen Emaki (picture scroll of farting battle) (Suntory Museum of Art collection) in which the characters compete on farts (*05).Hohi Gassen Emaki is a picture that is known by other names, such as Kachi-e, He Gassen Emaki, Hohi no Maki, and Hohi Gun. When browsing the Union Catalogue of Early Japanese Books of the National Institute of Japanese Literature, it is found that similar works have been acquired by the Waseda University Library and Tohoku University Library (Kano Collection), of which the artist is said to have been Toba Sojo Kakuyu, Sadanori, or Seiken (*06).

Going forward in time, Shinno Emaki (picture scroll of Shennong)

acquired by the Hyogo Prefectural Museum of History can also be traced to this farting battle.

acquired by the Hyogo Prefectural Museum of History can also be traced to this farting battle.

In any event, such nonsensical picture scrolls about farting were enjoyed broadly to some extent among people in power who played role as a cultural axis in the mid-15th century.

If, hypothetically speaking, the difference in the ages between Takamuko no Hidetake (main character of the two-volume Fukutomi Zoshi) and his daughter (supporting character in Hohi Gassen Emaki) is, say, 30 years, it is possible that there was an ancestral Fukutomi Zoshi (a so-called ‘alpha version’) at the beginning of the 15th century, or dating back even further.

Hyogo Prefectural Museum of History Collection Shinno Emaki

Hyogo Prefectural Museum of History Collection Shinno Emaki

-

*01: The period of production of the Cleveland Museum of Art version is thought to be the Kamakura Period, according to the database

that is run by the organization that owns the scroll.

For main reference literature regarding Fukutomi Zoshi, please refer to the site below for details.

that is run by the organization that owns the scroll.

For main reference literature regarding Fukutomi Zoshi, please refer to the site below for details.

Hyogo History Station (Digital Exhibition) Collection of Medieval Picture Stories > Reference Literature

- *02:Sakakibara Satoru “Goyo-eshi Kano-ha no Kenkyu” Kajima Bijutsu Kenkyu (Annual report, No. 14, Separate volume) 1996.

- *03:Minobe Shigekatsu “Fukutomi Choja Monogatari Honbunko” Densho Bungaku Kenkyu No. 22, 1979.

- *04:Postscript in 4th year of Hoto (1452). Fukutomi Zoshi Kotobagaki Dankan (Kokawa-dera Engi Shihai no Uchi) (Imperial Household Archives).

- *05:Sakakibara Satoru “Hohitan Sandai ,” Suntory Museum of Art Collection No. 2, 1987.

- *06: “He Gassen Emaki” (Waseda University Library Collection) Volume 1, drawn by Tosa Omi, 1846

Kachi-e (Waseda University Library Collection) Volume 1, 1807

Kachi-e (Waseda University Library Collection) Volume 1, drawn by Eikaishu, 1822

Tohoku University Library (Kano Collection) Hohi no Maki Volume 1

Two types of two-volume scrollsAlthough the Shunpo-in version and Cleveland Museum of Art version, which are the oldest versions produced in the mid-15th century, are both two-volume scrolls, there are actually small differences that can be found throughout the two versions.

For example, the presence of a man in kariginu clothes running to the watchtower in the fifth scene (*07), whether the black decoration on the wooden door of the Lieutenant General’s residence is a diagonal lattice or split diamond in the fourth scene, whether the curtain on the shelves of the store located on the main street in the sixth scene is made of bamboo grass or tachibana, and whether there is a wicker fence at the doctor’s residence in the twelfth scene (*08) have already been pointed out in prior research.

When looking thoroughly at the design of the scrolls, there were also other differences, such as the direction in which the chopsticks that have been placed on top of the cutting board are facing in the first scene, whether there is a rough-woven fence made of pampas grass in the fifth scene, whether there is a washhouse and flowing water by the well in the sixth scene, and whether there is a women’s straw hat in the tenth scene (thirteenth scene for the second part of Hyogo Prefectural Art Museum version).

Tokyo National Museum Collection 1st paragraph

Tokyo National Museum Collection 1st paragraphThese small differences are faithfully copied in manuscripts that were transcribed afterwards, and the two-volume version can be categorized further.

Using the details listed in Kokusho Somokuroku and Union Catalogue of Early Japanese Books

as a clue, we tried to categorize each of the transcriptions into the various versions. The works that are available as open data (published) on the Internet can be categorized as follows.

●Two-volume scroll: Shunpo-in version

as a clue, we tried to categorize each of the transcriptions into the various versions. The works that are available as open data (published) on the Internet can be categorized as follows.

●Two-volume scroll: Shunpo-in version- Kyoto Myoshinji Temple Shunpo-in (Important Cultural Property) Fukutomi Zoshi Volume 2

- National Diet Library Fukutomi Zoshi (First Volume) Volume 1, drawn by Kozan (1780 to 1840), 1818

- Imperial Household Archives Fukutomi (Ikezoko Series) One booklet

- Imperial Household Archive Fukutomi Zoshi (Parts One and Two) Volume 1, drawn by Awataguchi Naotaka, 1798

- Tokyo National Museum Fukutomi Zoshi Copy of Original Manuscript Volume 2

- Waseda University Library Fukutomi Zoshi Volume 2

- Hyogo Prefectural Museum of Art Fukutomi Zoshi (Part 2) (Version B) Volume 1 Original manuscript, drawn by Tosa Mitsuzane (1780 to 1850)

- Rikkyo University Library Fukutomi Zoshi formerly part of Yugaku-kan, Volume 2

※X. Jie Yang, Web Narration: The Tale of Fukutomi

- Library of Congress Fukutomi Zoshi Volume 1, drawn by Fujiwara Masanori, 1824

- Nishio City Iwase Bunko Library Fukutomi Zoshi Volume 1, drawn by Kishi Tadayoshi (Choton), 1844

- Tokai University Library (Toen Bunko) Fukutomi Zoshi One booklet, drawn by Ugawa, 1857

- University Art Museum, Tokyo University of the Arts Fukutomi Zoshi Part 2 Volume 1, drawn by Ariwara Shigetoshi (1828 to 1922), 1886

●Two-volume scroll: Cleveland Museum of Art versionLooking at the total number of scrolls, it can be said that the two-volume Shunpo-in version was mainstream, based on the overwhelming number of that version.

- *07:Muroki Yataro “Fukutomi Choja Monogatari (Jofukuji Collection) –Honkoku to Kaidai,” Mitsuda Kyoji Taikan Kinen Ronshu, Kanazawa University, College of Education, Japanese Language Research Lab, Professor Ryoji Mitsuda Memorial Retirement Project, 1969.

- *08:Matsunami Hisako “Considerations of Fukutomi Zoshi, annexed to Osaka Ohtani University Collection Fukutomi Zoshi Bibliographical Introduction and Reprint,” Journal of Osaka Aoyama University No. 9, 1981.

-

*01: The period of production of the Cleveland Museum of Art version is thought to be the Kamakura Period, according to the database

- 福富草紙の享受史①~兵博甲本(一巻本)とクリーブランド美術館本系~

-

Reception of Fukutomi Zoshi 1 Hyogo Prefectural Museum of Art’s Version A (one-volume scroll) and Cleveland Museum of Art versionCleveland Museum of Art version

The Cleveland Museum of Art version is a work that reveals the highly-skilled techniques of the artist, demonstrated by bright colors and firm, precise lines. As mentioned above, however, there are not many copies of this manuscript, and they are all thought to have been produced in the latter part of the Edo period.

The calligrapher of the Cleveland Museum of Art version that serves as the model is unknown, and the artists in the Edo Period who copied this manuscript are not artists by profession or status.

The artist of the version at the National Library of France is Jikoji Sanenaka. Jikoji was a courtier, and based on the similarity of the painting style, he is also thought to be the artist of Monkan Ajari Emaki (latter part of Edo Period) at the Waseda University Library (*09).Among the other Cleveland Museum of Art versions, there are some that are inscribed with “Fukutomi Gahon Myoshin-ji Kaifuku (-ji) –in Hizo Kotobagaki Shinkan is drawn by certain someone…,” such as in the Tohoku University Library version, which is a copy drawn in the Edo Period, and a manuscript in a private collection (signed in 1821) (*10). Although the inscription is signed by the Emperor, the illustrations were drawn by certain nobleman, leaving the artist gracefully unknown.

The Cleveland Museum of Art version implies that it was not necessary to pass down the identity of the authoritative artists by oral tradition.

In addition, the first part is not attached to this version. It is assumed that the Cleveland Museum of Art had made the second part independent on its own, or lost the first part a long time ago, resulting in an incomplete version (*11).

Even so, the designs of the second volumes of the versions at the Osaka Ohtani University and National Library of France, etc. are copies of the Cleveland Museum of Art version, and as the first volume of these versions is supplemented by copies of the Shunpo-in version, they are made up of two volumes.Although the number of replications is very few, it is evident that they are treasured.

This Cleveland Museum of Art version is thought to have formerly belonged to the collections of Reizei Tamechika (1823 to 1864) and Masuda Takashi (1848 to 1938) (*12). Before that, this version was thought to have been kept in great care in Kaifuku (-ji) –in, which is the sub-temple of Myoshin-ji, based on the inscription on the Tohoku University Library and private collection versions.

The inscription on the version held in a private collection further states, Bunsei Yonen Kanotomi Jugappi Nonoyama Yuizan Ihon Shakuran Kyogo / Aiga (Kao). Considering that Nonoyama Yuizan is probably an error for Nonoyama Kozan, this would mean that the second volume (whereabouts unknown) that accompanies the National Diet Library version, which is a Shunpo-in version, was borrowed and the inscription collated.

In the latter part of the Edo Period, although the sub-temples of Shunpo-in and Kaifuku-in were different, it appears as though two types of Fukutomi Zoshi—the Shunpo-in version and the Cleveland Museum of Art version—existed at Myoshin-ji.

Then, because the Cleveland Museum of Art version had different characteristics from the Shunpo-in version, and was not drawn by the same artist as the original manuscript, it became treasured.

- *09:Uchida Keiichi “Waseda University Library Collection Kitsune Emaki to Monkan Ajari Emaki,” Bulletin of the Waseda University Library No. 62, 2015.

- *10:Matsumoto Yasushi “Fukutomi Zoshi no Fukugen – Fukutomi Choja Monogatari no Kosei ni mo Oyobu,” Chuse Bungaku no Shomondai, Shintensha, 2000.

- *11:Matsunami Hisako, 1981.

- *12:National Diet Library Digital Collection, former collection of Masuda Takashi Daishikai Zuroku Dai 16 Kai, edited by Hirata Hisashi, 1912.

Derivation of one-volume scrollThe one-volume scroll that was derived from the two-volume version was proven to have diverged from the Cleveland Museum of Art version of the scroll. When looking at the published images in detail, all of the existing one-volume manuscripts are drawn in a design that is characteristic of the Cleveland Museum of Art version, and it is confirmed that the order of the paragraphs in this version all match.

The main manuscripts of the one-volume version that exist are as follows.

●One-volume version- Idemitsu Museum of Arts Fukutomi Soshi Emaki Volume 1 (*13) *The layout is one where the drawings and legends alternate, and the legends are short proses that do not specify the names of the main characters.

- Jofuku-ji Fukutomi Choja Monogatari Volume 1 (*14)※ Kanazawa City Official Homepage > Assets and History Inheritances in Kanazawa > Materials Related to Jofuku-ji Kitagata Shinsen

- Hyogo Prefectural Museum of Art Fukutomi Zoshi (Version B) Volume 1

- International Research Center for Japanese Studies Fukutomi Choja Monogatari One-volume scroll, drawn by Kamiya Sakae, 1775

- Shirayuri College Library Fukutomi Soshi Volume 1

- Toyo Bunko (Iwasaki Bunko) Fukutomi Zoshi Emaki Volume 1

Among the one-volume scrolls, the oldest ones in existence with complete legends are the Jofuku-ji scroll and the Hyogo Prefectural Museum of Art Version B scroll. Upon comparatively reviewing the images, both are thought to have been produced after the second half of the 16th century (latter part of the Muromachi Period), which is more recent than the Shunpo-in and Cleveland Museum of Art versions. At the very least, the Hyogo Prefectural Museum of Art scroll is oriented as having been created sometime at the end of the 16th century to the beginning of the 17th century (latter part of the Muromachi Period).

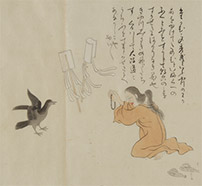

Utaichi・Tameichi(A version)

Utaichi・Tameichi(A version)The legend in the one-volume scroll of Fukutomi Zoshi was newly created in line with the second party of the antecedent two-volume Fukutomi Zoshi scroll. The contents diverge from the two-volume version, resulting in a unique world being formed.

For example, in the two-volume version, most of the supporting characters do not have names.

In the one-volume version, however, supporting characters are given names such as Myosai, Ogo, Wake no Kiyomaro, Utaichi, Tameichi, and Chamberlain, giving them personality.The main characters were originally given elaborate names and identities in the two-volume version. The successful old man was named Takamuko no Hidetake, and he was an artisan whose occupation was an incense burner. The unsuccessful old man was named “Fukutomi,” and he lived at Shichijo and was a priest there. Because of his occupation, he is nicknamed Fukutomi no Tone (Priest of Fukutomi), or Futone for short. His wife was named Futone ga Me (wife of Tomi Priest), and she is commonly known as Tone ga Me.

In the one-volume scroll, on the other hand, “Fukutomi” is the name of the successful old man, and the old man who fails is named “Bokusho no Tota.” The wife of the unsuccessful old man is named Oniuba, or Uba (semi-derogatory?!). Because these names were easy to understand, their character formation is emphasized.In such a way, in the one-volume scrolls, character formation of both the supporting characters and main characters is exaggerated, as they are made into commoners that have become generalized through their age and gender, ultimately stirring up comedy in this story.

Comedy is characteristic of the one-volume version, in which the legends are full of dirty jokes. A variety of words is used to describe the buttocks and crotch, such as idokoro, momojiri, fuguri, and oido. Direct references are used for farts (onara) and urine (shi (shi shi)) (similar books also refer to feces as “daiben”).

The one-volume scroll is also characterized by the abundant use of onomatopoeia. Kuruguru, nurunuru, hauhau, hitahita, neruneru, meramera, biyobiyo, shinchiyo, kirikiri, kototo (kotokoto), noronoro, yaseyase, shikajika, hishihishi, gabu, etc. are often used.

Such dirty jokes and onomatopoeia were probably not used in public by adult males. Many of these were the secret language of court ladies and words used by babies, and it has also been pointed out by Japanese linguists that other examples of use of these words are not seen until the beginning of the 17th century (*15).

In other words, in the one-volume version, it is thought that a person (maybe even a woman?) who was employed near an upper-class samurai family at the end of the 16th century to the beginning of the 17th century created the prose for this ‘monogatari’ story, based on the legends in the scrolls.

This overlaps with the period during which the Hyogo Prefectural Museum of Art’s Version B scroll was produced.In the mid-15th century, the class of people who enjoyed the ancestral two-volume Fukutomi Zoshi were those in power and who were at the cultural center. Starting at the end of the 16th century, however, the class who enjoyed the one-volume version changed to women.

A version 6th paragraph

A version 6th paragraph- *13: Idemitsu Museum of Art, ed. Yamato-e: Idemitsu Bijutsukan Zohin Zuroku, Heibonsha, 1986.

- *14: Muroki Yataro, 1969. Jofuku-ji zo: “Fukutomi Choja Monogatari” Gendaiyak, Kitagata Shinsen Kenshokai, 2006.

- *15: Someya Yuko “Fukutomi Zoshi no Nikeito no Honbun ni Tsuite – Sono Goi no Hikaku kara Kangaeru,” Ningen Bunka Kenkyu No. 1, 2003

Characteristics of one-volume scrollThe one-volume version of Fukutomi Zoshi was polished into a descriptive narrative making frequent use of baby talk and the secret language of court ladies, instead of moving the story forward through only soliloquys.。

The differences in the legends of the two versions are thought to have arisen due to there being a two-volume scroll in which there are no explanations of the picture scroll (Cleveland Museum of Art’s Fukutomi Zoshi Second Volume), and a one-volume version being created based on this (*16).In actuality, the Idemitsu Museum of Arts version, which is the oldest one among the one-volume scrolls, contains short legends resembling summaries, written on separate sheets inserted in between pictorial scenes, rather than being inserted as prose within the drawings. The name of the appearing character Fukutomi no Oribe is not even mentioned.

After a temporary in-between season in which there was a lack of legends, the legends of one-volume scrolls shifted toward a direction in which the story can be appreciated by reading it, more so than by looking at the drawings. The readers of the story were also anticipated as being children and women of the samurai class...Looking at it this way, rather than developing the prose so that it would be tinged with somewhat of a theater-like nuance, or so that it would explain the illustrations, it is instead accepted as a characteristic of the story. The prose is trying to be persuasive to beginners.

B version 12th paragraph

B version 12th paragraphFor example, in the second scene, the description of Bokusho no Tota’s life of poverty is very lengthy.

In the legend, it is indicated that the character kept covered from the cold wind, and this has been pointed out as being similar to a renga linked poem that was popular around the 16th century, which goes, keeping covered from the cold wind, the humble girl crouched by the fence (*17). This hints at part of literary art that is befitting for the readers of the story to be familiar with.

In the one-volume scroll, the bird that was the animal messenger of the gods (god of labor) in the two-volume version is the messenger of Kumano Gongen (tenth scene), and the bowl, which contains remarkable medicine in the two-volume version, consists of water (eleventh scene), suggesting that even detailed motifs are modified (*18).In addition, by using the terms zejo datsumono for a partition through which young girls peek (eighth scene), iko for a clothes-horse used to tread on hipbones (ninth scene), kinuta no ban for a rock used for Bokusho no Tota to place both hands on to express respect (eleventh scene), etc., pictorial motifs that were not mentioned in the legends of the two-volume version are explained using the names of the objects in the one-volume version (although they are interspersed with unique interpretations).

A version 11th paragraph

A version 11th paragraphFurthermore, what is interesting when thinking about the formation of the one-volume version is that in the final scene, Oniuba is depicted biting into Fukutomi no Oribe.

Her eyes were turned upwards, her mouth was opened broadly, as wide as her ears, and breathing as if in a rage, her body transformed into that of a snake (thirteenth scene)The expression “snake body” does not simply mean a snake as a living thing, but also takes on the meaning of the form of Kiyohime, who pursues her lover Anchin in Dojo-ji Engi

and becomes a serpent, or the form of Zenmyo, who chases her lover Gisho and becomes a dragon in Kegonshu Soshi Eden.

and becomes a serpent, or the form of Zenmyo, who chases her lover Gisho and becomes a dragon in Kegonshu Soshi Eden.

The formation of the original Dojo-ji Engi can be traced back to the initial part of the Muromachi Period, and became well-received to a certain extent from the period in which Important Cultural Property Dojo-ji Engi (Dojo-ji Collection) that was signed by Ashikaga Yoshiaki was produced.

The form of the snake, which escalated from serious love in these folk tales, represents in Fukutomi Zoshi an exchange in the capital of Kyoto, where there is no water, between an old man and elderly woman who do not even have any love between them. The gap between this parody and the original tales on which it is based invites laughter.

The one-volume version of Fukutomi Zoshi uses many baby words and court-lady language, and its prose was developed so that it can be easily accepted by readers. At the end of the 16th century to the beginning of the 17th century, when the one-volume version was established, there is no doubt that these picture scrolls brought good entertainment to the children and women of the samurai class, who were familiar with renga linked poems and shaji engi (picture scrolls of temples and shrines) such as Dojo-ji Engi.

- *16:Minobe Shigekatsu, 1979.

- *17:Minobe Shigekatsu, 1979. The legend for the second scene in the one-volume version is similar to the renga linked poem keeping cover from the cold wind, the humble girl crouched by the fence in the miscellaneous part of the 10th volume of Chikuba Kyoginshu that has a preface dated 1499, the miscellaneous part of Inu Tsukuba Shu edited by Yamazaki Sokan, and Zekku Hyoshaku.

- *18:Minobe Shigekatsu, 1979.

- 福富草紙の享受史②~兵博乙本(二巻本下巻)と春浦院本系~

-

Reception of Fukutomi Zoshi 2 Hyogo Prefectural Museum of Art’s Version B (two-volume scroll) and Shunpo-in versionTranscription of Shunpo-in version

When looking at the total number of existing manuscripts, it was mentioned earlier that the largest number of scrolls that still remain correspond to the Shunpo-in version.

Why were such copies produced?

Was it because this version just happened to be circulating?Existing manuscripts of this Shunpo-in version were transcribed in a concentrated manner, over a narrow range of approximately 100 years, between the latter part of the Edo period to the Meiji period, with the Imperial Household Archives version being the oldest, and the University Art Museum, Tokyo University of the Arts being the newest. This is the same as other existing manuscripts that are not dated but are of the same style of painting, and it is judged that these were produced in the latter part of the Edo Period.

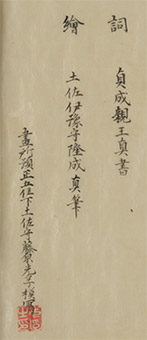

What is interesting is the historical trail of each manuscript. The original manuscript was handed down from Tosa Mitsunobu, and a process of producing copies can be observed, where the original was copied by a master artist of the Tosa school, which was further copied by disciples. Let’s try to check the historical trail of the existing manuscripts for which the artist and year of transcription can be confirmed.

First, the Imperial Household Archives version is a one-volume version that is a copy of Tosa Mitsunobu’s Fukutomi Zoshi copied by Awataguchi Naotaka as ordered by Matsura Ko, according to an inscription dating back to 1798. This was deemed as being a transcription related to forming the collection of Matsura Ko (or Matsura Kiyoshi, feudal lord of the Hirado Domain), who put in the order for the transcription. This version has gathered attention as an early example of Tosa Mitsunobu being asked to sign the original manuscript.

Next, the National Diet Library version was transcribed by Kozan (1780 to 1840) based on a version owned by Kano Tohaku (1772 to 1821) in 1818. The writing in India ink at the beginning of the scroll reads, Master Tosa Naiki, and there are explanatory notes nearby on Sumiyoshi Jokei.

![National Diet Library version [ Master Tosa Naiki ]](obj/img/zu_ext_1.jpg) National Diet Library version [ Master Tosa Naiki ]

National Diet Library version [ Master Tosa Naiki ]According to its inscription, the Library of Congress version is a work that was transcribed by Fujiwara Masanori, who was a disciple of Honda Tadanori (1774 to 1823), and who transcribed in 1827 a transcription produced by Honda in 1803 of a transcription made by Iitsuka Hiromi of an existing manuscript Sumiyoshi’s room of paintings. The inscription by Fujiwara Masanori in 1827 states that who wrote the transcript is unknown, but the artist of the original Fukutomi Zoshi is Tosa Mitsunobu.

The Nishio City Iwase Bunko Library version is an excerpt created by Kishi Tadayoshi (Choton: - 1857), from an existing manuscript that was kept as a treasure by Sumiyoshi Naiki in 1840, according to the preface in the transcription. Its title page and note at the beginning of the scroll also state, Fukutomi Otogi Zoshi <signed Tosa Mitsunobu> Sumiyoshi Naiki Zokan Kakinuki. The transcription also describes Honda Tadanori, who is well-versed in knowledge of court rules, acknowledging Tosa Mitsunobu as the artist.

The University Art Museum, Tokyo University of the Arts version is a transcription by the disciple Ariwara Shigetoshi (1828 to 1922) in 1886, using a transcription made by Arai Naoharu (Tadaharu), an artist of the Sumiyoshi school, as a model, which was in turn a copy of the copy drawn by Tosa Mitsunobu owned by Sumiyoshi Naiki.

The above is a summary of the basic history of the copies, according to bibliographical information and image information that have been published. Among these, the folklore of the manuscript drawn by Tosa Mitsunobu as seen in the Nishio City Iwase Bunko Library version has gathered attention as it completely matches the inscription dated 1827 in the Library of Congress version. Taking into view that the Library of Congress version originated from the copy made by Iitsuka Hiromi of an existing manuscript Sumiyoshi’s room of paintings, his master Sumiyoshi Hiroyuki (1705 to 1777) may have been involved in identifying the artist.

Up this point, it has been explained that copies were produced for the purpose of learning ancient paintings, or for use as memos or painting models for artists. This is because there are more than a few copies that are plain sketches or drawn in ink and wash, or where instructions for coloring have been written in. As with the Cleveland Museum of Art version, some were copied in order to learn the original form of picture scrolls by analyzing existing versions that are not mainstream.Behind the Shunpo-in version, however, there are four underlying factors: (1) A drawing model of the Shunpo-in version existed in Sumiyoshi’s room of paintings, (2) this drawing model was a copy of the version drawn by Tosa Mitsunobu, (3) there were times when it was thought to have been transcribed by Sumiyoshi Naiki (Jokei), and (4) the artist who newly transcribed this version was of the Sumiyoshi school.

The Fukutomi Zoshi that are presumed to have been drawn by Tosa Mitsunobu or Sumiyoshi Jokei have not been confirmed, regardless of the version. If this is so, transcribing the Shunpo-in version of Fukutomi Zoshi was an action to gain important items that guarantee the validity of the genealogy of artists who have succeeded Tosa Mitsunobu and Sumiyoshi Jokei.

By producing copies, (4) the artists of the Sumiyoshi school themselves have fulfilled a role of passing down the folklore of (2) and (3) as facts.

Binding errors in Shunpo-in versionNow let’s focus on the order of the pictorial scenes.

The story in the majority of the existing manuscripts of Fukutomi Zoshi reach a climax in the following order. The Cleveland Museum of Art version, all of the one-volume versions, and even among the Shunpo-in versions, those that are copies of the Sumiyoshi Naiki manuscript follow the order below.(9) Wife treads on husband’s waist → (10) Wife prays → (11) Old man defecates → (12) Wife begs for medicineHowever, there are two types of binding errors in only the Shunpo-in version.

In the Imperial Household Archives version and the Hyogo Prefectural Museum of Art version ‘B,’ the order of (10) Wife prays and (12) Wife begs for medicine are switched.(9) Wife treads on husband’s waist → (12) Wife begs for medicine → (11) Old man defecates → (10) Wife praysIn the Rikkyo University Library version and a manuscript in a private collection (1775, drawn by Kano Yosenin Korenobu), paragraph (9) Wife treads on husband’s waist is inserted between (11) and (10) based on the order of the Imperial Household Archives version = Hyogo Prefectural Museum of Art Version B (*19).

(12) Wife begs for medicine → (11) Old man defecates → (9) Wife treads on husband’s waist → (10) Wife praysThe issue of handling these binding errors has not yet been decided on in the history of studying the manuscripts. Even so, since even the pictorial scenes and proses in the drawings in the Imperial Household Archives version and the Hyogo Prefectural Museum of Art Version B have been supplemented, it is inferred that the manuscripts were collated in such a way intentionally, in pursuit of a natural development of the story.

The eighth paragraph was enhanced, featuring a naked and shivering old man being stared at by a large crowd of people.

B version

B versionIn addition, in the Hyogo Prefectural Museum of Art version ‘B,’ there is an excerpt in the latter part, even for the alternative version (same two-volume, Shunpo-in version) with different coloring and that is made up of both a first volume and second volume. It is clear that artists in the latter part of the Edo Period tried to learn something from these picture scrolls that were created hundreds of years earlier.

The manuscript that served as the model for the first half of this version is presumed to be an existing manuscript owned by Takashima Chiharu (1777 to 1859), who was an artist of the Tosa school, based on the transcribed preface Chiharu no Hon. The artist who transcribed this was Tosa Mitsuzane (1780 to 1852), and this copy was further transcribed by his disciple, an artist of the Tosa school, resulting in the Hyogo Prefectural Museum of Art version ‘B.’

According to the inscription by Tosa Mitsuzane, the legend Chiharu no Hon was deemed to be written by Sadafusa Shinno, while the illustrations were drawn by Tosa Takanari. This opinion matches with the contents of the note of authentication signed by the calligrapher in the Shunpo-in version.

At the same time, however, the Imperial Household Archives version, which follows the same order of pictorial scenes, was thought to have been drawn by Tosa Mitsunobu.The lore of the artists is wavering.

During this era, Shukojusshu and Kogaruiju by Matsudaira Sadanobu (1759 to 1829) were successively compiled as major projects. In particular, in Kogaruiju, drawings and pictures scrolls from the past were comprehensively gathered and reproduced according to each motif; even 16 drawings from Fukutomi Zoshi were included. In the table of contents, it is listed, Fukutomi Zoshi Myoshin-ji Collection, drawn by Mitsunobu (*20). Thus, it was known that the Shunpo-in version was deemed to have been drawn by Tosa Mitsunobu.

This lore started shifting, possibly due to the judgment of Takashima Chiharu, who was well-versed in knowledge of court rules, as indicated in the preface of the Hyogo Prefectural Museum of Art Version B.

These are slightly different circumstances than the phenomenon of the Sumiyoshi Naiki version, which served as the drawing model for the Library of Congress version and the Nishio City Iwase Bunko Library version, which are based around the Sumiyoshi school, having continued to be conveyed as being drawn by Tosa Mitsunobu.Apart from historical facts, it is also the truth that the lore of such artists played an important role in the social and cultural spheres of that time. Works by Tosa Mitsunobu or Tosa Takanari increased interest in Fukutomi Zoshi, as they were handed down as lore, and at the same time, this lore was reexamined, and the works were actively reproduced.

B version 8th paragraph

B version 8th paragraph- *19: Yoshihashi Sayaka “Shiryo Shokai – Rikkyo Daigaku Zushokanzo Fukutomi Zoshi Emaki” St. Paul’s Rikkyo University The Papers of Japanese Literature No. 8, 2008.

- *20:Tokyo National Museum, ed. Kogaruiju: Chosa Kenkyu Hokokusho Tokyo National Museum, 1990.